The northern lights — also known as the aurora borealis — is a magical display of colour and light, visible across northern skies. It’s one of the most magnificent sights on Earth.

But to understand where the phenomenon originates, we have to look 150 million kilometres away, to the surface of the sun. Here, sunspots and the rhythm of the solar cycle have a profound influence on the aurora.

But what are sunspots? How do they relate to the solar cycle? And what effect does this solar activity have on our planet?

Let’s take a look.

What is a sunspot?

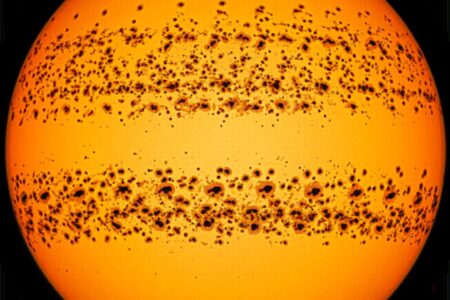

Sunspots are dark dots that appear on the surface of the Sun. They’re cooler than the surrounding area but still incredibly hot (around 3,500°C).

These spots mark places of intense magnetic activity and they come and go — sometimes lasting hours, sometimes months. Their size varies too, with some sun spots as large as Earth.

Scientists have been interested in sunspots for over a thousand years. These dark patches help to predict other types of solar activity. They also tell us whether the dancing colours of the northern lights are likely to make an appearance.

What causes sunspots?

Scientists are still studying how sunspots are formed. But they believe that these dark patches are caused by the Sun’s magnetic field.

The Sun is a huge ball of charged gas, constantly on the move. As it spins, its magnetic field gets tangled and twisted. In some areas, this magnetic pressure blocks the flow of hot gases from the sun’s interior, forming a cooler, darker patch: a sunspot.

Each sunspot has a central, darker region called the umbra, surrounded by a lighter area called the penumbra. They often appear in pairs and groups, and their number rises and falls in sync with the Sun’s natural rhythm — known as the solar cycle.

Sunspots and the northern lights

The northern lights are caused when solar particles from the Sun collide with Earth’s atmosphere. And we get the brightest and more colourful aurora displays following a big solar explosion, called a coronal mass ejection (CME).

Sunspots don’t directly cause CMEs or the northern lights. But they’re a key sign that a period of intense solar activity is on the way.

The area around a sunspot is very volatile. As the Sun’s magnetic field stretches and shifts, it can suddenly snap and realign in a violent burst of energy. This sometimes causes a CME, an explosion that throws lots of solar particles out into space.

When a CME is directed towards Earth, it can trigger geomagnetic storms and the northern lights can blaze across the sky in vivid waves of green, pink, red, and violet.

The more sunspots on the surface of the Sun, the more likely it is that a CME will appear. So aurora hunters are always very excited when lots of those dark spots start to form.

The link between sunspots and the solar cycle

The number of sunspots on the surface of the Sun rises and falls in a pattern, known as the solar cycle. This cycle generally lasts for around 11 years. But it’s not totally predictable — a cycle can be as short as 8 years and as long as 14.

Scientists use sunspots to assess where the Sun is up to in its 11-year cycle. These dark patches are a sign of solar activity, visible from Earth.

What causes the cycle of solar activity?

The solar cycle is caused by the Sun’s magnetic field. Every 11 years or so it does something remarkable. The Sun’s magnetic poles flip — north becomes south and south becomes north.

This marks the start of the solar maximum — a time of intense solar storms, lots of sunspots and spectacular northern lights displays.

Over the following years, activity on the Sun calms and we eventually reach the solar minimum. This is a period of few sunspots and less dramatic solar activity.

Can you see the northern lights during the solar minimum?

You have an excellent chance of seeing the northern lights during the solar maximum. Around the peak of the solar cycle, the aurora borealis regularly lights up the night sky.

But that doesn’t mean it’s impossible to see the northern lights when solar activity dips.

While there are fewer sunspots and fewer solar explosions during the solar minimum, charged particles are still steadily streaming from the Sun, out into space.

They travel on the solar wind, which is released by coronal holes on the surface of the sun. These holes can form at any time but they’re especially common around the time of the solar minimum.

The solar wind flows continuously in our direction and can trigger beautiful aurora displays without the help of a CME.

To see the aurora during this time, it’s best to travel north, to the Arctic Circle — and to seek out clear night skies, away from light pollution.

How else do sunspots affect us on Earth?

Sunspots tell us that a bright aurora is probably on the way — and, if there are lots of sunspots, it’s a clue that the northern lights may be seen further south, in places like Scotland, Denmark and Germany.

Sunspots also act as an early warning system for other, less magical, Earthly events. Because sunspots are linked to intense solar activity and geomagnetic storms, they help to predict:

- Electrical grid disruption. Powerful geomagnetic storms can create electric currents in electrical grid equipment, leading to voltage instability, equipment damage, and power outages.

- Satellite and communication problems. Charged solar particles can interfere with satellite electronics, causing them to temporarily stop working.

- Radio transmission issues. Solar activity can disrupt radio waves, particularly around the poles. This can impact aircraft communication and emergency broadcasts.

- GPS errors. Solar interference can skew navigation systems, leading to minor inaccuracies on your smartphone GPS and even nautical navigation systems.

How many sunspots are on the sun today?

Right now, we’re part way through solar cycle 25. And we’re around the peak of the solar maximum. That means there’s a lot of sunspot activity.

You can take a look at what’s happening on the surface of the Sun on the NASA website — and view sunspot data for today, provided by the Royal Observatory of Belgium.

Why it’s a great time to book a northern lights holiday

Right now, we’re at the peak of the northern lights 11-year cycle. Solar activity is intense and there are lots of sunspots. So you have a great chance of seeing the northern lights on an aurora holiday.

Want to see the aurora for yourself? Why not take a look at our tailor-made northern lights holidays for inspiration?:

- Northern lights holidays to Sweden

- Northern lights holidays to Iceland

- Northern lights holidays to Finland

- Northern lights holidays to Norway

Sunspot and solar cycle FAQs

How hot is a sunspot?

A sunspot is cooler than the surrounding surface of the Sun. This is why it appears as a dark spot. The temperature of a sunspot is around 3,500°C (6,300°F). The surrounding surface of the Sun is around 5,500°C (10,000°F).

How big are sunspots?

Sunspots are huge — many of them as big as a planet. The average sunspot is roughly the size of Earth but particularly large sunspots can reach 100,000 kilometres in diameter.

How long do sunspots last?

Sunspots can last for hours, days or months. Smaller sunspots tend to be short-lived, while larger sunspots last longer.

How do you view sunspots on the sun?

Viewing sunspots can hurt your eyes. You have to use a special solar telescope or a standard telescope fitted with a certified solar filter. Alternatively, you can look at live images of the Sun taken by satellites or observatories.

How long is a solar cycle?

A solar cycle lasts for around 11 years. Scientists start counting the new solar cycle from the solar minimum. Solar activity increases until the solar maximum, at the peak of the cycle. Solar activity then decreases until it returns to the solar minimum.

What is the solar minimum?

At the solar minimum, there are few sunspots and relatively little solar activity. This is the least active point in the Sun’s cycle.

What is the solar maximum?

The solar maximum is the peak of solar activity — a time when there are lots of sunspots, solar flares, and coronal mass ejections. This means the northern lights are more likely to be visible here on Earth.

When is the next solar maximum?

In 2025, we’re experiencing a solar maximum. This is a time of intense solar activity and beautiful aurora borealis displays. The next solar maximum will occur roughly 11 years from now.

Who discovered sunspots?

Galileo is thought to be one of the first astronomers to view sunspots through a telescope. He used his telescope to project an image of the Sun onto a screen and watch sunspots being carried across the surface of the Sun.

But Galileo wasn’t the first scientist to understand that sunspots existed. Astronomic records from Ancient China show that sunspots were being observed and recorded as early as 28 BCE.